by Rita J. King

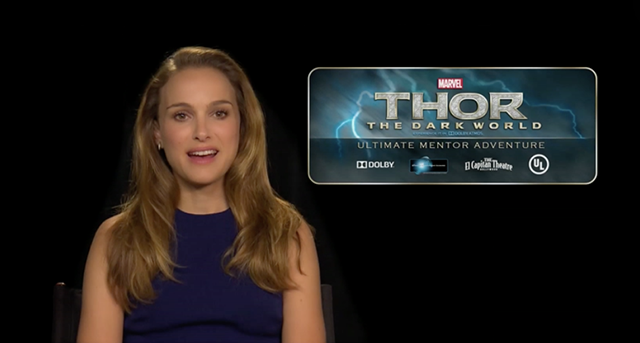

Remember when Natalie Portman and Marvel teamed up to offer girls a life changing opportunity to explore science?

Ten brilliant girls won, and one of them recently reached out to The Curiosity Review. An aspiring engineer named Ashley Smith was selected to win an exciting opportunity to fly out to California and meet women with STEM careers.

“In the fall of 2012 I entered the 'Thor: The Dark World' Ultimate Mentor Adventure,” Ashley told The Curiosity Review. “The other winners and I were all so inspired by this adventure and have been working on putting a website together that can be used as a resource and tool for girls who want to learn a little more about STEM or see if it is for them.”

Natalie Portman plays astrophysicist Jane Foster in the film, and kicked off the “life-changing opportunity” of the contest with this message to girls: “The truth is, I really do love science, and this role gave me an opportunity to explore science and all its possibilities.”

All of the girls who won the competition have been working hard to promote STEM in their own communities.

“I myself am putting together a 5-day summer camp that I will be conducting with three different schools in my area,” Ashley said.

She asked me if I would be open to doing an interview that she could share with followers of her adventure, which you can see here. I was thrilled to do it, and wanted to share it here on The Curiosity Review for others who are committed to science for the benefit of humanity.

Ashley Smith: Can you tell us a little about your background? Where you grew up, what education do you have, a summary of your resume, did you always want to do what you are doing now, when did you start to become interested in STEM, what internships/volunteering?

Rita J. King: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York until I was 12, and then my family moved upstate to a very small town. The experience of having a very urban and then a very rural upbringing helped me understand the impact of culture on people’s perspectives.

When I was a child, my father was a student at Columbia University. He let me skip school one day and go with him to his classes. In his physics class, I learned about quarks, and suddenly realized that there’s so much around us that we can’t directly perceive. That afternoon, in his French class, we saw a black and white film. I’ve loved science and art ever since.

Education is a lifelong activity – I love to learn and I consider the entire universe a classroom. Everybody on this planet is a teacher, and we can all learn something from each person we encounter. I started working and volunteering at a very young age. I was the president of entrepreneurship club in elementary school. I was student council president. My friend from high school recently posted a documentary I directed in high school. We investigated local officials, budgets, and policy decisions. To do this, we needed a mix of skills from math to public speaking.

AS: What exactly IS your job? What do you do on a day to day basis?

RK: I co-direct Science House in Manhattan along with James Jorasch, who is an entrepreneur, early-stage investor in a number of STEM companies, and inventor. Science House is a seven-story townhouse that we have designed as a cathedral of the imagination. Our focus is working with companies to help them build teams that can create the future they can imagine.

I work with leadership teams all over the world, helping them to create strategies during this time of constant change. Most large companies, regardless of industry, face the same problem: an Industrial Era mindset as they segue into the Intelligence Era.

The Industrial Era still permeates everything we do, from education to work. Our brains are good at understanding tangible objects like jet engines. The Intelligence Era is coming, and it’s made of much more nebulous concepts, like algorithms, data, and code.

To help our clients make a distinction between the two eras and create strategies that are unique to this period, I created a way to frame the time in between. I call it the Imagination Age.

I am also a jewelry designer and artist. I make necklaces called Treasure of the Sirens designed from the actual amphorae found in the ancient shipwrecks in the sea around the island in the Tyrrhenian Sea where my great-grandmother was born. These are 3D printed in precious metals. And I make Mystery Jars, which are small glass jars filled with tiny objects, fragments, and memories from around the world. I am also a writer and a futurist. I served as futurist at NASA Langley’s think tank, and I am currently a futurist for the Science and Entertainment Exchange of the National Academy of Sciences. I work on film and TV projects, inventing novel characters, scenarios, story architecture and future technologies.

AS: How does STEM relate to your job? How do you use the information you learned from your degree in your job?

RK: I study as many areas of science as I can all the time. I love neuroscience, biology, physics, astronomy, all of it. I use what I’ve learned constantly in my work, and I am always finding connections between things that help me see everything I do in a new light. I took many science classes in college, but I have a liberal arts degree. This served me in my desire to piece things together and communicate more effectively.

AS: Have you faced any discrimination or challenges being a woman in a STEM field? If so, how did you deal with it? Do you have any advice for up-and-coming women in STEM?

RK: Discrimination is an act of criminal negligence and ignorance. It actively prevents individuals from accessing opportunities they’ve earned, and at the same time it holds all of society back at a time when we need the best and brightest people working together to solve problems. People who are willing to challenge the status quo often face discrimination. In many places, women still don’t have access to the education required to achieve deep understanding and freedom in life.

Women continue to face a difficult battle, but we’re doing it with measurable success, which means we will continue to face opposition. When we stop facing opposition, it probably means we’ve begun to stagnate. Undermining discrimination requires constant vigilance and discipline, because our brains accept the social biases we’ve been conditioned to believe since birth. We get bombarded with messages constantly. Part of the way we can undermine discrimination is to live by example and help share stories about others who live by example, counter to the dominant narratives.

We are social beings, hard-wired to want social acceptance. But it is unreasonable to expect support from everyone all the time. All people are born into specific circumstances at a specific time and place, and the rules in each culture impact our lives before we even know how to sit up on our own. These rules can change over time, due to the effort of people who value progress enough to fight for it. The effort we put into undermining discriminatory rules can benefit someone else in the future. One of the reasons I love working with the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science is because the organization is deeply committed to science for the benefit of humanity, and very focused on equally supporting women scientists who contribute significantly to this mission.

AS: What is the best and worst part of your job? What do you look forward to in your job on a day-to-day basis? What do you wish you could change?

RK: I look forward to learning every day.

AS: How do you balance your work and personal life? Any secrets or advice you’d like to share?

RK: There’s very little division between my work and life. I only take on work I’m passionate about, but that means I often work nights, weekends, and holidays. I try to make up for it when I can. I collaborate with my husband, so it’s a lot of togetherness. We are very different people in some ways, but similar at the core.

Everything comes with tradeoffs. Life is short and a lot of what we do, we do because we think we are supposed to. My trick is that I view life as an adventure, and I stay open to opportunities, people, places, and ideas that show up along the way.

AS: What do you define success as?

RK: Maintaining equilibrium while moving forward and growing every day. Improving the world through curiosity, creativity, and commitment.

AS: What is one personality trait that you think is universally important for a successful career?

RK: Regardless of the field, practicing the scientific method helps. Learning to pay attention is extremely important. Learning to make connections between things. Being open to criticism and learning from it instead of taking it personally. This doesn’t come easily and it requires discipline. Some critiques are not accurate. You need to consider the source. But sometimes, the comment that feels like an attack is just what you needed to assess yourself and your weaknesses more accurately. Mastery, even over yourself, is mostly a function of overcoming your weaknesses to improve as a human being. Empathy is also critical. This is the ability to understand someone else’s position. Empathy enables us to support other people more fully. It also creates a strategic advantage, for example, when it comes to paying attention to someone else’s motives.

AS: Who was a mentor to you throughout your career (can be more than one!)? What did they teach you? How did they impact your life?

RK: A lot of my work follows an offbeat path. I’ve had mentors in lots of different fields at different times. The key to mentorship is to pay attention to other people, whether it’s a five-year-old kid, someone famous, or a woman who has been retired for a decade. Everyone has something to teach you, and you may not realize at the time that you’re in the presence of a mentor.

AS: What do you think is the best advice you've ever received? What advice would you give your younger self if you had the chance? What’s one piece of advice you can pass on to us?

RK: There’s a book called Finite and Infinite Games by James Carse, in which the author makes the argument that finite games are those with clear opponents, rules, a winner and a loser, and infinite games are those that are played just for the sake of keeping the game going and bringing more people into it. At some points in your career, you may think you’re playing a finite game. Maybe you want to beat another candidate for a job, or close a deal. But my advice is to think of your body of work as an infinite game, and to take your work seriously without taking yourself too seriously. We are all works in progress, and we can work together to achieve things that are barely imaginable.