Weizmann’s Prof. Yair Reisner, pioneer of a revolutionary bone marrow transplant technique, was part of a small, elite medical team that treated those most sickened by radiation

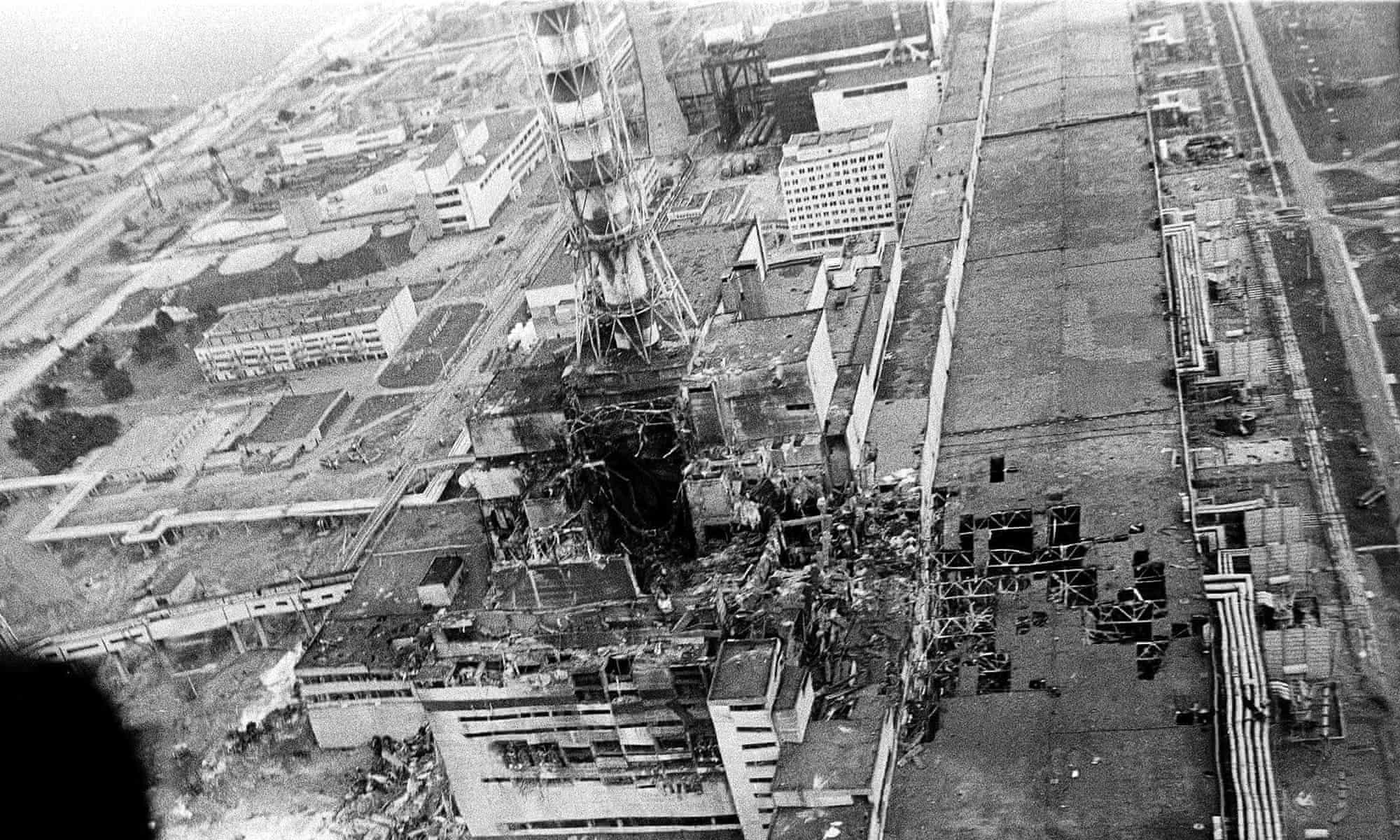

The Chernobyl nuclear power plant catastrophe on April 26, 1986 has always loomed large in our imaginations, particularly for those of us living through the Cold War.

Last year, the event was front and center yet again – and new generations learned about it – when HBO’s limited series, “Chernobyl,” took us through the disaster, step by harrowing misstep. The show also reminded us of the heroes, from the scientists trying to reach the truth to the workers who sacrificed themselves.

We recently learned of another hero: the Weizmann Institute’s own Prof. Yair Reisner, who wrote in Time about his experience as part of an small, elite group that traveled to the USSR to treat Chernobyl’s victims.

At the time, Reisner already had a global reputation for his pioneering technique that enabled bone marrow transplants between mismatched donors and recipients. Before his breakthrough, the parties had to be a genetic match, and untold numbers of lives were lost for lack of a suitable donor.

Reisner’s method involved “cleaning” the bone marrow; because radiation severely damages the marrow – which produces our blood cells – the method could be crucial for treating Chernobyl’s victims. Thus, he was invited to join the medical team (of course, he accepted) and was soon in another world: Moscow’s now-infamous Hospital No. 6, which was featured in “Chernobyl.” It held the patients most sickened by radiation, such as the firemen who went into the burning, damaged reactor to try and halt its collapse.

As Reisner told The Los Angeles Times in 1986, he found that (surprisingly) “the Soviet doctors he worked with had copies of all his scientific papers”; however, they did not have the expertise or facilities needed to help the radiation victims. And in addition to the hospital’s outdated equipment, the building itself seemed to be crumbing round them.

“I had performed the procedure of cleaning bone marrow dozens of times, but never under such conditions,” Reisner recalled. But the doctors were grateful for his help and eager to learn, and he was able to train them to perform his technique so that they could keep conducting transplants after he returned home.

What ultimately happened to the patients? Unfortunately, many did not make it – their bodies were simply too damaged by radiation – but the ones who did survive were among those who underwent Reisner’s technique.

The experience transformed medical understanding of how to treat people severely impacted by radiation, but Reisner notes another lesson as well: that in the case of nuclear war, even the highest level of medical sophistication and planning would be futile when it came to treating victims.