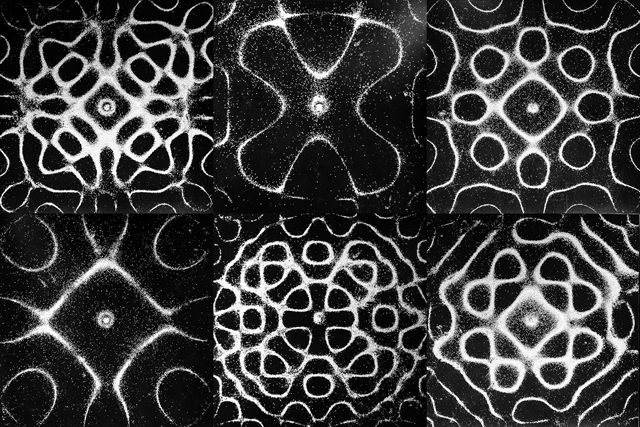

Photo credit: Chris Smith, CC

Everything that moves emits a frequency and makes a sound. Even bubbles.

Some people have a hard time hearing (why?) even under the best of circumstances. Others see sound without trying, and some even have chromesthesia, a form of the neurological condition synesthesia in which a person feels music in colors. Pharrell Williams is a synesthete, and he believes it gives people a futuristic ability.

On an episode on ABC-TV's "Nightline," Williams recalled that when his family moved to the suburbs and he encountered a wonderful band teacher, he knew music was for him. "It just always stuck out in my mind. And I could always see it. I don't know if that makes sense but I could always visualize what I was hearing. It was like...weird colors."

If the rest of us want to see the impact of sound on physical matter, we have options, such as exploring the work of Meara O’Reilly. Her site is a cabinet of auditory curiosities, from a fascinating catalogue of Illusion Songs to Chladni Singing.

“Chladni patterns were discovered by Robert Hook and Ernst Chladni in the 18th and 19th centuries,” O’Reilly wrote. “They found that when they bowed a piece of glass covered in flour, (using an ordinary violin bow), the powder arranged itself in resonant patterns according to places of stillness and vibration. Today, Chladni plates are often electronically driven by tone generators and used in scientific demonstrations.”

Designer Demian Conrad was also inspired by Chladni Singing, so much that he created a graphic identity for the Camerata de Lausanne around the concept.

“I greatly admire and respect classical musicians, who devote themselves body and soul to bringing us emotions,” Conrad wrote. “Because of my ingrained curiosity, I often ask myself the question: how can something invisible, like music, be graphically portrayed?”

Some artists visualize songs, but even musical scores are a form of visualization. At the end of last year, musician Beck released a new album, Song Reader, that was made up entirely of sheet music. This completely silent album has to be played by the audience in order to be heard.

In his review of Beck’s work, Malcolm Jones wrote:

“But we’re begging the question big time: is the music any good? Slick answer: it’s as good as you make it. Beck argues that ‘one can learn the songs contained here as written, but ultimately they’re only sketches. They’re meant to invite interpretations and improvements above and beyond the way they are on paper.’”

But even as sketches go, there’s still a lot of room for even more creativity, particularly across cultural boundaries. Artists since the 1960s have played with the boundaries of sheet music.

“When a musician writes a score that must be mechanically carried through, compelling the interpreter to follow it as if he was a machine… what is the sense to make it for a human being if it can be made for a machine?” John Cage once said. “A music score that imposes such a severity has no sense. Ideas must be free and the musicians who will play must be creative.”

A visual conversation can be global, but it also can be intimate, right down to a single beat of sound etched in platinum on the ring finger of your beloved.

For those of you who are still curious, here’s a technical exploration of the neural mechanics of auditory-visual synesthesia. Think you might be a synesthete? Take a test.