Maybe you heard about it on NPR. Or the BBC. Or your local paper or news station. The world paid attention to the news that a novel cancer treatment is sending blood cancer patients into "dramatic remission."

This is just the latest thrilling progress in the treatment, which uses a patient’s own immune system to defeat cancer. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, which conducted the new trials, reports that "Twenty-seven out of 29 patients with an advanced blood cancer … experienced sustained remissions," and that "some of the patients in the trial, which began in 2013, were originally not expected to survive for more than a few months because their disease had previously relapsed or was resistant to other treatments," but "today, there is no sign of disease."

This headline-making, hope-giving breakthrough was born in the 1980s at the Weizmann Institute of Science, where Prof. Zelig Eshhar first saw the potential of autoimmune cancer therapy. He developed a treatment that employs what he called "T bodies" – white blood T cells outfitted with receptors that specifically seek out and identify tumors, promoting their destruction.

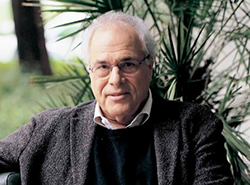

Prof. Zelig Eshhar

In principle, T cells can carve through cancerous tissue; however, they often lack the ability to recognize the mutated cells. So Prof. Eshhar genetically modified the T cells to become T bodies by adding synthetic molecules called CARs (chimeric antigen receptors). The CARs can identify tumors, and the T cells then attack and destroy the cancer cells.

Over the course of two decades, Prof. Eshhar’s T-body technology went from being a revolutionary idea that works in the lab to being a medical treatment that works in humans. In August 2011, as reported in The New York Times, University of Pennsylvania researchers revealed that they had successfully used Prof. Eshhar's approach in a pilot trial of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The patients were treated with their own T cells, which were genetically engineered based on Prof. Eshhar’s method. In December 2012, the researchers reported that 9 of 12 leukemia patients in the ongoing clinical trial responded to the therapy. The participants included 10 adult patients with CLL and two children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). "This study provided a proof of concept for the potency of our T body therapy – previously shown to work in mice, it has now proved beneficial in cancer patients,"Prof. Eshhar said.

In March 2013, investigators at New York's Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center published the results from a clinical trial in which they used a method similar to the one in the University of Pennsylvania study. This time, the subjects were adults with chemotherapy-resistant B-cell ALL. In stunning results, there was a 100 percent success rate: all five of the patients who received genetically modified versions of their own T cells achieved complete remission. Clinical trials of T-cell therapy are also taking place elsewhere, such as the National Cancer Institute's Center for Cancer Research.

Even as other researchers began building upon Prof. Eshhar’s basic research, he continued his own investigations into new methods of delivering T-body therapy. In 2005, for example, his team succeeded in using T bodies to treat prostate cancer that had spread to bone marrow tissue in mice.

And in a 2011 study in mice, the team created T bodies from a donor pool of T cells, rather than T cells extracted from the individual patient – and the cancer cells were destroyed. This is important because if this method works as well in humans as it does in mice, it could lead to a therapy that utilizes an off-the-shelf pool of T cells equipped with receptors for zeroing in on different types of cancerous cells. Such a cancer therapy would be much more accessible and affordable, and truly an example of how basic science research is science for the benefit of humanity.