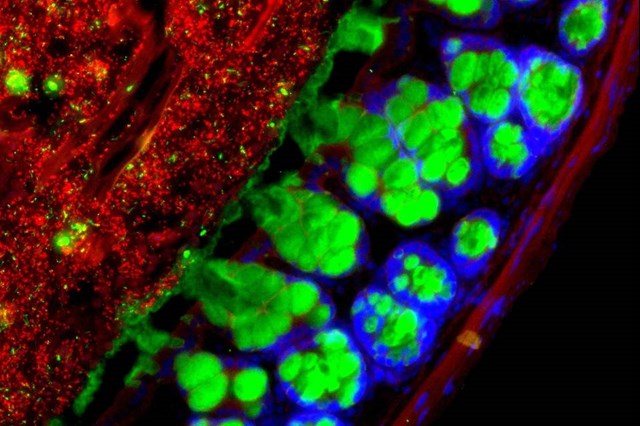

A healthy community of microbes in the gut maintains regular daily cycles of activities. PHOTO: WEIZMANN INSTITUTE

New research sheds light on how eating and sleeping habits can contribute to disease by disrupting the bacteria in the digestive tract

New research is helping to unravel the mystery of how disruptions to the bacteria in our gut, caused by an unhealthy diet or irregular sleep, can lead to a number of diseases.

Such research could someday result in new treatments for obesity, diabetes and other metabolic conditions by restoring the health of the gut-microbe community, known as the microbiota. Researchers are exploring how to do this through individualized diets and mealtimes or other interventions.

When gut microbiota are healthy, they maintain regular daily cycles of activities such as congregating in different parts of the intestine and producing metabolites, molecules that help the body function properly. A disruption of the gut’s circadian rhythms is communicated through the bloodstream and upsets many of the body’s other circadian clocks, especially in the liver, one of the main metabolic organs, according to a study by Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science published in the journal Cell in December.

The gut’s circadian rhythms and those in other organs “dance together in a very profound way and go up and down in coordination with each other,” says Eran Elinav, a physician and immunologist at the Weizmann Institute and one of the study’s lead investigators. “By controlling the gut microbiota, you can modify many physiological capabilities” throughout the body, he says.

In earlier studies, researchers at the University of Chicago Medical Center and other academic centers have found that gut microbiota in mice are significantly disrupted by high-fat foods, such as those included in typical Western diets. The time of day when people eat also can throw microbiota off-kilter.

The American Heart Association warned in a scientific statement in January that irregular eating habits, such as skipping breakfast and eating late at night, may disrupt the gut’s circadian rhythms and increase the risk for diabetes, heart disease and other conditions.

Studies also have found that microbiota rhythms are compromised in people who do shift work and those with sleep apnea. Such people are at increased risk for developing metabolic conditions. “We now believe the microbiome may be one of the missing links to explain why these individuals may be more susceptible to conditions,” says Eran Segal, a computational biologist at Weizmann and the study’s other lead investigator.

The Weizmann researchers found that many of the genes in the liver lost their normal circadian rhythms or took on completely new rhythms in response to disruptions in the gut. The liver’s ability to break down acetaminophen, a common pain reliever and fever reducer, also was compromised as a result of the organ’s disrupted rhythms, says Dr. Segal.

The Weizmann research went beyond previous studies in the field in identifying interactive pathways in the body on a molecular and genetic level, says Eugene Chang, a professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. The study is “a tour de force in showing how complex this interaction is,” says Dr. Chang, senior author of a 2015 study in the journal Cell Host & Microbe that also showed how gut-microbe rhythms coordinate with those of other organs.

There is no single solution for returning microbiota to a healthy state. Dr. Chang believes resetting a person’s metabolism by implanting select microbes or microbe-produced metabolites could become an effective way to help prevent or treat some metabolic conditions.

Being able to predict how different foods affect people’s blood-sugar level, based on the composition of their microbiota, also could potentially help maintain metabolic health. The Personalized Nutrition Project, another study led by Drs. Elinav and Segal, studied 1,000 people and about 50,000 meals and snacks for a week. People’s metabolisms varied widely, it found. After eating ice cream, for example, blood-sugar levels would soar for some participants while hardly budging for others, Dr. Segal says.

Some of the participants were tested to see if adjusting the content and timing of food consumption could regulate metabolism. The study, published in Cell in 2015, succeeded in normalizing blood-sugar levels in some patients with prediabetes, Dr. Segal says. Further research will explore whether customized diets and mealtimes can also restore overall gut health, he says.

The technology to analyze gut microbiota, and algorithmic programs to predict the impact of food on blood sugar, have been licensed to a startup called DayTwo Inc., to which Drs. Elinav and Segal act as consultants.