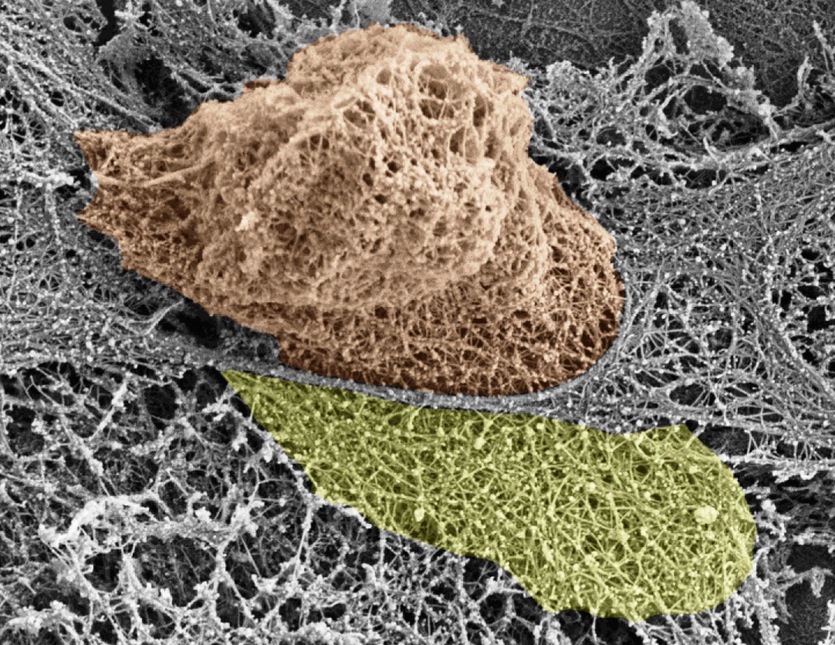

When it infiltrates a blood vessel wall, a T cell pushes thin filaments out of the way – but these quickly reassemble. Credit: BARZILAI ET AL / CELL REPORTS 2016

They’re the door-to-door salespeople of the body (but you want to let these ones in)

When immune cells need to attack an invader or simply patrol your organs, they must slip in and out of the bloodstream. But how they do this hasn’t been fully understood – until now.

A team from Israel and the UK watched different types of immune cell shimmy through a blood vessel wall. And instead of the blood vessel cells contracting to let them through, it appears immune cells squeeze their way through, breaking a few cell structures which are rapidly replaced.

The work was published in Cell Reports.

Thousands of immune cells, such as white blood cells (also called leukocytes), are nudging their way through your blood vessels each second. When a part of your body becomes inflamed, for instance, molecules signal for help to leukocytes passing by in the bloodstream.

When they come across such a signal, leukocytes stop and slip between cells that line your capillaries, called epithelial cells. Epithelial cells are tightly wedged together to form a physical line of defence. But the damage leukocytes leave behind is insignificant. How?

Some cell biologists thought epithelial cells might contract a little to let immune cells pass, a bit like opening sliding doors, while others suspected the immune cells pushed their way through, like a pushy door-to-door salesperson.

Sagi Barzilai and Sandeep Kumar Yadav, both from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and colleagues decided to see what was going on.

They stopped the contracting machinery of the epithelial cells but found leukocytes were still able to penetrate. “That was our big surprise,” says Ronen Alon, also from the Weizmann Institute.

So using other cellular tweaks and microscopy, they eventually saw the leukocytes used their nucleus (which harbours important genetic information and, in leukocytes, is particularly pliable) prodded by their own cell machinery to squeeze between cells.

The leukocyte extended a thin protrusion between endothelial cells – think of it as the salesperson’s foot. As more of the cell squeezed through, eventually a lobe of the nucleus was squashed through too (our salesperson’s leg).

As the nucleus lobe deformed the surrounding cells, endothelial cell scaffolding called actin snapped and stress fibres stretched, signalling the cells to open the gap. The leukocyte’s own internal machinery pushed the nucleus forwards until it – and the rest of the cell – popped through.

The gaps were only four or five microns wide – the width of the nucleus – and any bits of broken actin [were] quickly and easily replaced.

The work is relevant to cancer, as tumour cells, with their relatively stiff cell nucleus, are less able to infiltrate the bloodstream or hop out of it.