Minute traces of ancient plants release human history to scholars' probes.

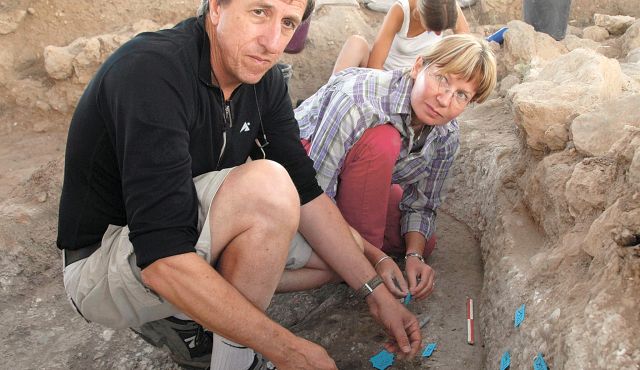

An archaeological dig in Tel Tzafit, the hometown of biblical giant Goliath. Photo by Richard Whiskin

Gath, the capital city of the Bible's bad guys as well as the hometown of Goliath, is known today as Tel Tzafit. Not far from Kiryat Gat, Tel Tzafit has been excavated for 16 years now by Prof. Aren Maeir of Bar-Ilan University.

But while thousands of artifacts and vessels have been unearthed, including a four-horned altar, as well as just this year, huge fortifications, doctoral candidate Yotam Asher of the Weizmann Institute is concentrating on a few faded white patches of rock.

Until a few years ago most archaeologists would not even have considered these to be archaeological finds. The focus on them could symbolize the new road the discipline has taken in general, and Israeli archaeology in particular.

Known as microarchaeology, this new field use precise scientific instruments to interpret more elements of the ancient record, making it more complex and at times, more human. Instead of great kings vanquishing cities, pillaging, murdering and being murdered, it also tells the story of cultural transformation and of simple urban dwellers.

Called phytoliths, the white spots are what remains after most of a plant has decayed, as a kind of skeleton made of minerals.

Asher is doing his Ph.D. on what phytoliths can teach us. Those at Tel Tzafit are what is left of plants that lived 3,300 years ago. A preliminary look under the microscope shows that one spot is what remains from a pile of domesticated wheat while another is of unidentified wild plants. "It's possible that in one place was a sack of hay and in another, a sack of wild plants, or that these are plants that were on a roof that collapsed," Asher says.

Not far from the white spots sits Prof. Steve Weiner of the Weizmann Institute, who is considered the father of microarchaeology.

On the day Haaretz visited Tel Tzafit Weiner took two soil samples, and after brief processing that included crushing them with a small mortar and pestle he subjected them to his mobile infrared scanner. In two minutes, a graph appeared on his laptop screen. According to the molecular arrangement, Weiner says, "There's no doubt that this ground was used for burning on a regular basis." In other words, now we know where the kitchen was in the dwelling near where the phytoliths were found.

But how will such new research tools affect archaeologists' interpretations of history? "Take for example the story of aliyah to Israel, which has been underway for the past 200 years. In thousands of years, when archaeologists look at this, they'll think it happened in one year. We know it's more complicated, that there were all kinds of mini-aliyahs," says. "It's not that we understand the entire past ... the picture is much more complex," he adds. On any given day there about 150 people digging at Tel Tzafit — archaeologists, students, soldiers, volunteers and paid workers.

Dr. Amit Dagan, who is in charge of one of the excavation areas, says the students come "from Hungary, South Africa, South Korea, England and Ireland. There's no better melting pot than this."

The Canaanites established the first city at Tel Tzafit about 3,500 years ago, as attested by the walls discovered this year, which are significant because Canaanite cities in this period were rarely walled, Maeir says.

The Philistine city was built in the 12th century B.C.E. and flourished for 300 years. Philistine culture was complex and included elements of the culture of the kingdom of Judah as well as the Canaanite and Aegean cultures.

Unfortunately for people who support a historical interpretation of events depicted in the Bible, no external evidence of the capture of Gath by David or Solomon has been found.

The most dramatic event in Gath's history was its conquest and destruction in 830 B.C.E. by the Aramean king Hazael, whose campaign against nearby Jerusalem is recorded in 2 Kings, which according to Maeir brought on enormous geopolitical change. "On the surrounding hills, to this day, 2,800 years later, you can clearly see the remains of the Aramean siege lines," Maeir says.

About a century later the city suffered another blow, mentioned in Amos 1:1 — an earthquake, which may be evident in the angle of fallen walls at the site.

The city was eventually abandoned for around 2,000 years, until Saladin built a fortress there in 1191.

The Tel el-Safi village was established later. It was abandoned and destroyed in 1948. Today Tel Tzafit is a national park.

In the realm of classical archaeological finds, in addition to the walls, the city's cultic area, where the four-horned altar was found last year, continues to emerge. Nearby were vessels that show the cultural melting pot that was Gath — delicate pottery from Cyprus, baking trays from Judah and other finds from foreign shores.

"We're trying to piece together a puzzle with 10,000 pieces, says Maeir. They don't have all the pieces, Maeir says, but "now, at least, we have the tools to better understand how they connect."

Click here for article.