REHOVOT, ISRAEL—September 29, 2020—The odors we give off are a sort of body language – one that may affect our relationships more than we realize. New research from the lab of Prof. Noam Sobel at the Weizmann Institute of Science suggests that this “chemical communication” may extend to human reproduction as well. The study, which was published in eLife, found that women who suffer from a condition known as unexplained repeated pregnancy loss (uRPL) process messages concerning male body odor – especially their husband’s – in a different way than other women. These findings may point to new directions in the search for causes and prevention of this poorly understood disorder.

Prof. Sobel and his team in the Institute’s Department of Neurobiology thought that some cases of uRPL could be related to a human variation on the Bruce effect, named after its discoverer Hilda Bruce, who found in 1959 that when pregnant mice are exposed to the body odor of a male that did not father the pregnancy, they will almost always abort. Why this occurs is not fully understood, but the common rationale is that the female “chooses” to abort because the chemical message is that a new, “more fit” male is in town.

Could a similar effect occur in women? A remarkable estimated 50% of all human conceptions, and some 15% of documented human pregnancies, end in spontaneous miscarriage. Ethical considerations obviously prevented the researchers from repeating the Bruce experiments in humans; the team instead sought circumstantial evidence.

For the Bruce effect to occur in mice, the female must remember the body odor of the fathering male. To test for this in humans, the researchers presented participants with three odorants: one extracted from a t-shirt worn by their spouse and two from t-shirts worn by other men. They found that women with uRPL were able to identify their spouse by smell, while the control women could not. When retested with ordinary odorants to see if those with uRPL simply had a better sense of smell overall, they tested only marginally better.

The ability of uRPL women to identify their spouse by smell was remarkable: In a part of the experiment where the women did not know what odors they would be smelling, “several of these women said ‘oh, my husband’s in here’,” reports research student Reut Weissgross, who co-lead the study. This never happened – even once – with the control women.

Further testing suggested that the uRPL women are not just better at picking out the smell of their spouse, but may experience men’s body odor in a different way altogether. When asked to rate the body odor of men on various scales, including by standard scales for pleasantness and intensity, but also such factors as fertility or sex appeal, the uRPL-affected women were unique in the way they described and graded the smells, and differed significantly from the control women in their answers.

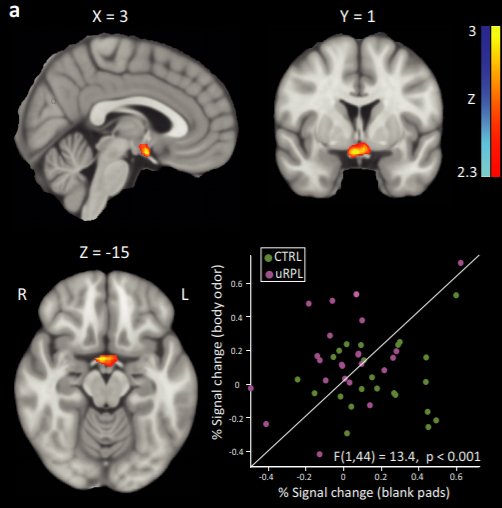

In the final phase of the research, the experimenters used both structural and functional brain imaging to study the participants. The structural imaging revealed that women with uRPL have smaller olfactory bulbs, which are the initial brain-relay for smell. Using functional imaging, the scientists found an increased response to men’s body odors in the hypothalamus of women with uRPL. The hypothalamus is a brain region that participates in, among other things, coordinating pregnancy and overall hormonal regulation, and plays a key role in the Bruce effect in mice.

“It seems these losses of pregnancy may be ‘unexplained’ because physicians are looking for problems in the uterus, when they should also be looking in the brain, and particularly the olfactory brain,” says Weissgross. Prof. Sobel cautions: “Correlation is not causation, so our findings do not prove in any way that the olfactory system, or body odors, cause miscarriage. But our findings do point to a novel and potentially important direction for research in this poorly managed condition.”

The study was co-lead by Dr. Liron Rozenkrantz, Reut Weissgross, and Dr. Tali Weiss, all in Prof. Sobel’s lab, and was conducted in collaboration with Prof. Howard Carp, head of the uRPL clinic at Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer.

Prof. Noam Sobel’s research is supported by the Azrieli National Institute for Human Brain Imaging and Research, which he heads; the Norman and Helen Asher Center for Human Brain Imaging; the Nadia Jaglom Laboratory for Research in the Neurobiology of Olfaction; the Rob and Cheryl McEwen Fund for Brain Research; and Sonia T. Marschak. Prof. Sobel is the incumbent of the Sara and Michael Sela Professorial Chair of Neurobiology.