The findings enabled Weizmann Institute researchers to grow lymphatic cells in the lab – for the first time in the world

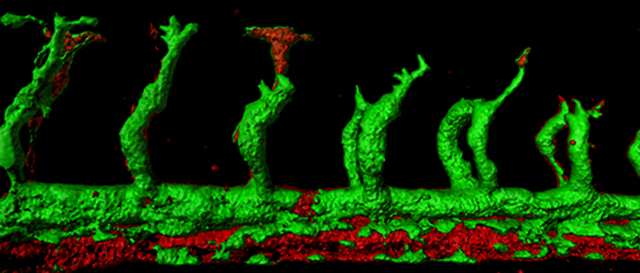

Zebrafish embryos with fluorescent “glow in the dark” blood vessels helped solve the mystery of the origin of the lymphatic system

For more than a century, scientists have debated the origins of the lymphatic system – a parallel system to blood vessels, and which serves as a conduit for everything from immune cells to fat molecules to cancer cells. This issue has now been resolved by Dr. Karina Yaniv of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Department of Biological Regulation. In a study reported in Nature, she and her team revealed how the lymphatic system develops in the embryo and – in a world’s first – managed to grow lymphatic cells in the lab.

Some scientists had claimed that the lymphatic system was derived from specialized stem cells called angioblasts, whereas others had argued that it originated by the differentiation of pre-existing embryonic veins. The latter model had ultimately become the accepted view.

But as the research in Dr. Yaniv’s lab progressed, it became clear that scientists on both sides of the argument had been correct: Lymphatic cells do indeed grow from veins, but they originate from a niche within the vein that harbors angioblasts.

Dr. Yaniv’s research group.Sitting from the right: Lihee Asaf, Dr. Karina Yaniv, Tal Lupo, and Julian Nicenboim. Standing: Dr. Yogev Sela.

In the initial stages of the research project, Dr. Yaniv’s team members Julian Nicenboim and Dr. Guy Malkinson obtained images of developing zebrafish embryos, whose transparent bodies make it possible to document embryonic development in real time over several days. The scientists then played the movies backward, to identify the point at which the lymphatic system began to form. To their surprise, they discovered that the cells that give rise to lymphatic vessels always originated in the same part of the embryo’s major vein. In that spot, the scientists found a niche of angioblasts, those same cells that a hundred years earlier were thought to be the source of lymph vessels, but then were neglected.

An in-depth genetic analysis, performed with the participation of graduate students Tal Lupo and Lihee Asaf, pointed to a gene called WNT5B, which was revealed to be the factor prompting stem cells to differentiate into lymphatic cells. When postdoctoral fellow Dr. Yogev Sela added WNT5B to human embryonic stem cells, the cells indeed differentiated into lymphatic cells – the first time such cells had ever been grown in the lab. “We started out by imaging zebrafish, and ended up finding a factor that makes it possible to create lymphatic cells,” says Dr. Yaniv. “That’s the beauty of research in developmental biology: The embryo holds the answers, and all we have to do is watch and learn.”

Aside from the feat of answering the longstanding question of how the lymph system arises, understanding how it forms and develops can provide important insights into disease, from the metastasis of cancer to the abnormal accumulation of lymph fluids, particularly in the wake of surgery to remove cancerous tumors.

This research was performed in collaboration with the laboratories of Prof. Itai Yanai from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Dr. Jacob Hanna of Weizmann’s Department of Molecular Genetics, and Prof. Nathan Lawson of the University of Massachusetts.

Dr. Karina Yaniv’s research is supported by the Henry Chanoch Krenter Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Genomics; the Karen Siem Fellowship for Women in Science; the Carolito Stiftung; the Adelis Foundation; the David M. Polen Charitable Trust; and the estate of Georges Lustgarten. Dr. Yaniv is the incumbent of the Louis and Ida Rich Career Development Chair.