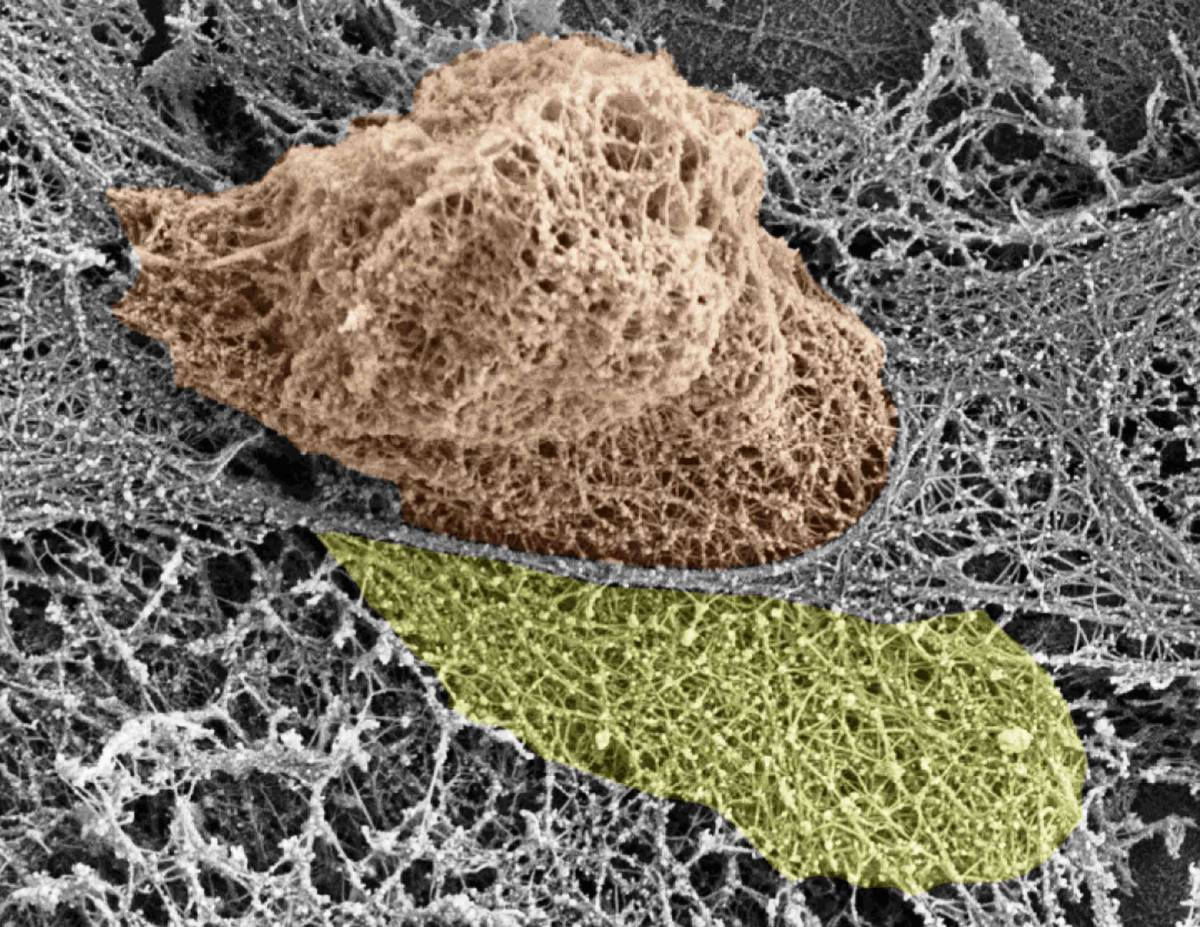

White blood cell squeezing through endothelial cells (grey) on its way out of the blood vessel walls. The actin cytoskeleton of both cells is exposed; the white blood cell nucleus is shown in brown and the large actin-rich extension that dismantles the endothelial actin is shown in yellow

White blood cells push their way through barriers to get to infection sites

One of the mysteries of the living body is the movement of cells – not just in the blood, but through cellular and other barriers. New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science has shed light on the subject, especially on the movement of immune cells that race to the sites of infection and inflammation. The study, published in Cell, revealed that these cells – white blood cells – actively open large gaps in the internal lining of the blood vessels, so they can exit through the vessel walls and rapidly get to areas of infection.

Prof. Ronen Alon and his group in the Weizmann Institute’s Department of Immunology discovered how various white blood cells push their way through the lining of the blood vessels when they reach their particular “exit ramps.” Using their nuclei to exert force, they insert themselves between – as well as into – the cells (called endothelial cells) in the vessel walls. Dismantling structural filaments within the cytoskeletons – the internal skeletons – of the endothelial cells creates the large holes, which can be several microns in diameter.

Prof. Alon explains that the nucleus is the largest, most rigid structure in the cell. When driven by motors specifically engaged for this function, it is tough enough to push through the barrier imposed by the blood vessel walls.

The scientists tracked the cytoskeletons of endothelial cells as they were crossed by immune cells in real time, the behavior of the nuclei of various white blood cells during active squeezing, and the fate of the various types of actin fibers that make up the endothelial cell skeletons. The researchers used a number of methods, including fluorescence and electron microscopy, in collaboration with Dr. Eugenia Klein of the Institute’s Microscopy Unit; a unique system in Prof. Alon’s lab for simulating blood vessels in a test tube; and in vivo imaging with Prof. Sussan Nourshargh of Queen Mary University of London. The results of this research, conducted in Prof. Alon’s lab by research students Sagi Barzilai and Francesco Roncato and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Sandeep Kumar Yadav, were recently reported in Cell Reports.

Common wisdom in this field had held that the endothelial cells must help immune cells squeeze through by contracting themselves like small muscles, but the present study found no evidence for such contraction-based help. Prof. Alon says: “Our study shows that the endothelial cells, which were thought to be dynamic assistants in this process of crossing of blood vessel walls, are really more responders to the ‘physical work’ invested by the white blood cell motors and nuclei in generating gaps and crossing through blood vessels.”

Significance for cancer research

In addition to increasing the basic understanding of how the various arms of the immune system reach their sites of differentiation and activity, these findings may aid in cancer research. “We believe that small subsets of metastatic tumor cells have the ability to adopt the mechanisms used by immune cells to exit the blood vessels into the lungs, the bone marrow, the brain, and other organs. If this is true, we might be able to identify these subsets and target them before these cells leave their original tumor sites and invade distant organs,” says Prof. Alon.

Prof. Ronen Alon’s research is supported by the Herbert L. Janowsky Lung Cancer Research Fund; Mr. and Mrs. William Glied, Canada; and Carol A. Milett, Aventura, Florida. Prof. Alon is the incumbent of the Linda Jacobs Professorial Chair in Immune and Stem Cell Research.